It started with one magical model, no dedicated space and a few staff who saw the transformative power of molded plastics, printed layer by layer into a physical, life-size anatomical representation.

This 3D-printed replica of conjoined twins was the big bang from which Mayo Clinic’s 3D anatomical modeling practice has exploded.

“We started doing 3D printing about 17 years ago at Mayo Clinic for a complex case involving congenital twins. And it’s expanded over that time frame to encompass every surgical subspecialty,” says Jonathan Morris, M.D., medical director and co-founder of the 3D Anatomic Modeling Unit at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. “The reason it started all in-house is because we have subspecialty expertise in each part of the process. We had these complex problems, and we found that 3D printing aided in understanding them in a three-dimensional, life-size way that 2D images could not.”

Growth and development

Over 17 years and counting, the practice has expanded in size and scope, with increasing square-footage dedicated at Mayo Clinic to the 3D Anatomic Modeling Unit in Rochester and new and growing spaces in Arizona and Florida.

Each group is led by dedicated physicians, researchers, engineers, technologists and more, all committed to ensuring these valuable tools are available to any physician, surgeon, researcher or educator who needs them. In addition to Dr. Morris, Rahmi Oklu, M.D., Ph.D., is medical director of the Arizona group. Elizabeth M. Johnson, M.D., is medical director of the Florida team, and Robert Pooley, Ph.D., is the technical director in Florida.

The space in the Joseph Building at Mayo Clinic Hospital – Rochester, Saint Marys Campus is now about 8,000 square feet of manufacturing space with 16 staff and 15 3D printers that use a broader array of materials than were available in 2006. The 3D Anatomic Modeling team in Arizona has about 1,000 square feet, nine printers and two staff, and the team in Florida has nearly 1,000 square feet, with additional space to allow for further expansion to almost 1,200 square feet, 10 printers and two full-time staff and five additional team members.

This growth ensures Mayo is able to meet the needs of the patient, Dr. Morris says. “The space and the technology we have are unique for a healthcare institution, but it only exists because the needs of the patients dictated it.”

At Mayo Clinic in Arizona and Florida, the lab spaces are newer endeavors than in Rochester, reflecting the surging demand for patient-specific models and cutting guides for individualized care — and for advancing the science. Arizona and Florida had 3D printers, but they now have homes to allow for continued growth.

“It’s nice. It’s brand-new, there’s a lot of orange — I like orange,” Dr. Oklu says of the new space in Arizona, which opened in 2020.

Where it started

In Rochester, the 3D Anatomic Modeling Unit finished construction in 2021 on an expanded space that better accommodates what has become a booming practice — with about 900 models and 1,200 cutting guides produced each year.

“Mayo Clinic is really setting the path for others to follow,” says Adam Wentworth, a senior engineer in the Rochester 3D Anatomic Modeling Unit. “The development of this space could not have occurred without the vision from administration and the passion of the leadership of Dr. Jonathan Morris and Dr. Jane Matsumoto, who started the lab. The effort that they have put in outside of their normal working hours to lift up the lab and communicate its capabilities to everyone else and the surgical champions who have communicated the benefit of anatomic modeling were also a huge factor in the success of the lab.”

He says the returns on the investments are apparent every day.

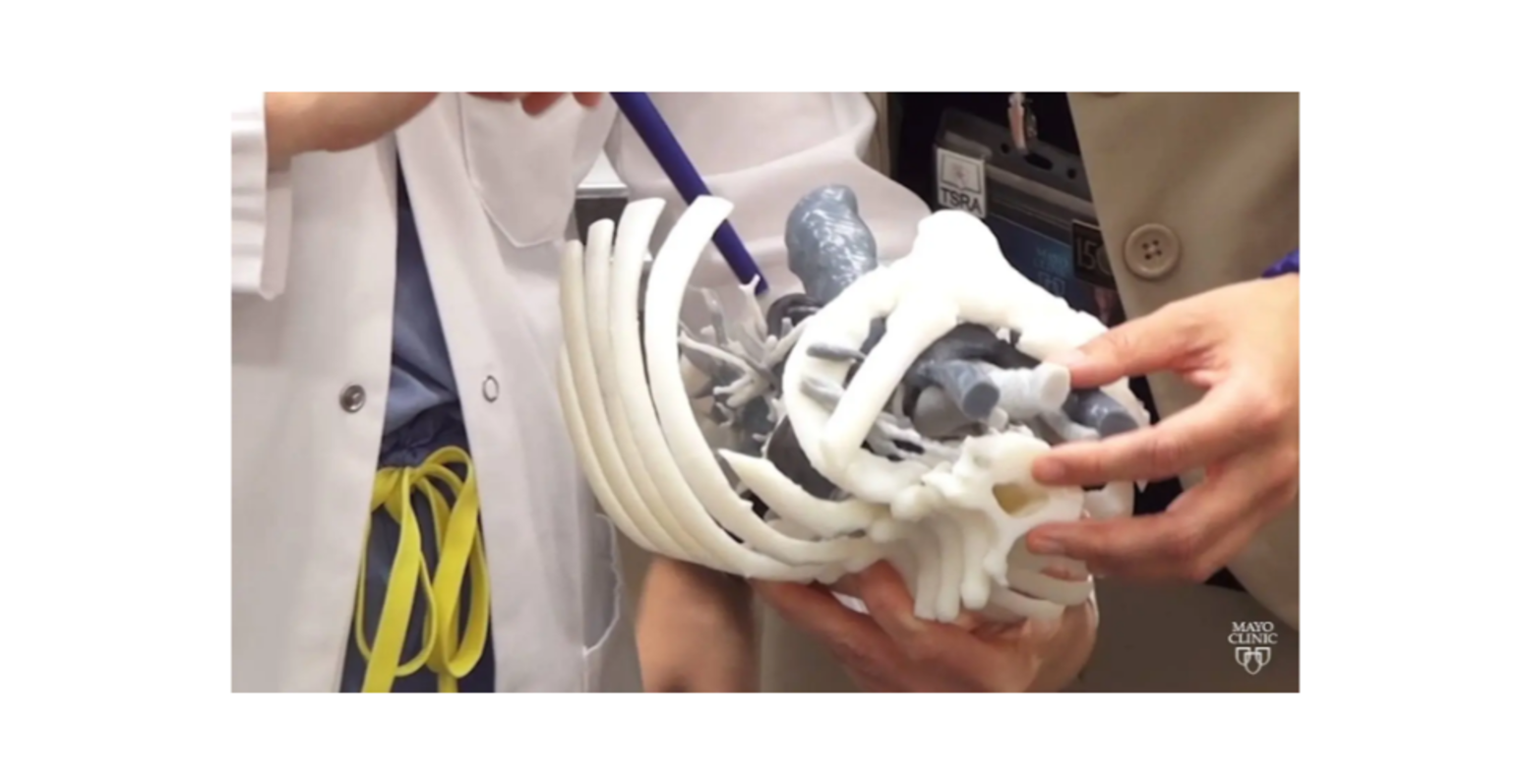

“Physicians and surgeons are able to have the life-size 3D model in their hands,” says Tori Sears, another engineer in the Rochester 3D Anatomic Modeling Unit. “They can visualize where a tumor is exactly located within the anatomy that’s usually covered up by soft tissue. They make measurements right on the model and can better understand through haptic perception where that tumor is located, what adjacent critical structures are nearby and what is the best approach to minimize procedure times.”

Dr. Morris says it is important to have the 3D anatomic modeling practice as part of the Department of Radiology.

“When you combine everything together and you centralize it within the Department of Radiology, you can serve just not one specialty, you can serve all of them,” he says. “We’re an integrated team of people who are coming together to solve complex surgical problems. And we’re using engineering, 3D printing, custom medical device manufacturing and surgical expertise all together, instead of each one of us working apart.”

Where it’s going: Arizona

Dr. Oklu says 3D printing in Arizona is a “three shields” endeavor, touching education, research and the clinical practice.

With the debut of the new space, Dr. Oklu had intended to provide opportunities for staff to learn about 3D printing — how the printers work and how to order models and guides. After being sidelined by the pandemic, that effort is restarting.

“My plan is to go to every department to present what we do and what we could do,” Dr. Oklu says. “I want to open it up so people can learn what 3D printing is. Everyone’s curious, they just don’t know how to do it.”

He says the lab won’t stray from what Florida and Rochester do on the clinical side. “I try to help, whatever the request is.”

Research, however, is where Dr. Oklu sees his lab distinguishing itself from the other sites. His roles as a clinician investigator and the head of the Laboratory of Patient-Inspired Engineering overlap with his work with 3D printing. Among the many advancements he is exploring are about a dozen biomaterials that he hopes can stop bleeding, deliver targeted therapies to tumors, embolize blood vessels and more.

“We’re trying to use our materials to treat aneurysms. The hardest part is making a model,” he says. “We’re thinking maybe we can 3D print the aneurysm to tell us that our biomaterial is working.”

Dr. Oklu sees mostly incremental changes on the horizon in additive manufacturing. “The materials are going to change, the printers are going to change — they’re going to become faster, more widely available, maybe even cheaper — but it will still be the same 3D-printed models.”

Biomaterial printing, though, will be the next revolution in 3D printing, he adds, and he hopes the research he is doing in printing aneurysms will help spur that advancement.

“Continued investment will ensure 3D printing remains an important part of patient-focused care at Mayo Clinic,” Dr. Oklu says. “We’ve come a long way, but we’re just getting started.”

👉 Mayo Clinic’s 3D printing operations growing, changing medicine along the way – Mayo Clinic News Network